Whilst the world grapples with the impact of Covid-19 and tries to unravel all the unknowns, it is important to decide what lessons we want to take forward with us into the post-Covid-19 world. (As Donald Rumsfeld, former United States Secretary of Defence, once infamously said “… there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”)

Covid-19 has demonstrated the positive results when we agree on what is important, which begs the question; what else might we achieve with a common will and purpose? What indeed do we want to achieve and what world should we strive to create? Are all the jobs that have been lost those the world most needs or might our labour and creativity be better applied elsewhere; which parts of the economy will we want to restore and what might we choose to let go of? Those are some of the questions that warrant attention and thought.

Then what about the things that have been vetoed, including hugs and handshakes? A frightened public has largely accepted a level of curtailment of civil liberties that previously would have been hard to justify. A precedent is being set for:

- The tracking of people’s movements at all times (because of coronavirus)

- The suspension of freedom of assembly (because of coronavirus)

- The military policing of civilians (because of coronavirus)

- Censorship of the Internet (to combat disinformation, because of coronavirus)

- Compulsory vaccination and other medical treatment, establishing the state’s sovereignty over our bodies (because of coronavirus)

- The classification of all activities and destinations into the expressly permitted and the expressly forbidden (you can leave your house for this, but not that). The essence of totalitarianism, seen as necessary, because, well, coronavirus.

It remains to be seen whether or not these current controls become permanent.

According to the FAO, five million children worldwide died of hunger in 2019, 14 times more than had died from Covid-19 by late May 2020. But no government declared a state of emergency or asked for a radical alteration to our way of life to save the children. This is not to say the actions now are inappropriate, rather to ask why, if are we able to engage our collective will to stem this virus, can we not also attempt to address other grave threats to humanity?

The reality is that, in the face of world hunger, addiction, autoimmunity, suicide, or ecological collapse, we as a society do not know what to do. Then here comes a contagious epidemic, a crisis for which control works: quarantines, lockdowns, isolation, hand-washing; control of movement, control of information, control of our bodies. Unlike so many of our other fears, Covid-19 offers the feasibility of a plan.

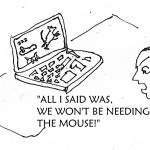

Covid-19 will eventually subside, but the threat of infectious disease is permanent. Our response to Covid-19 will shape our lives for the future. We must anticipate that new viruses will emerge and it is not hard to imagine that emergency measures will become normal, so as to try to forestall the possibility of another outbreak. That means that the temporary changes in our way of life may become permanent and we could live in a society where nearly all of life happens online: shopping, meeting, entertainment, socializing, working, even dating. Is that what we want?

The mantra of “safety first” stems naturally from a value system that makes survival the top priority and depreciates other values like fun, adventure, play, and the challenging of limits. Public life, communal life, has been dwindling. Do we want to live in a world where human beings never congregate because it keeps us safer? Do we want to wear masks in public all the time? Do we want to be medically examined every time we travel? How much of the quality of life do we want to sacrifice at the altar of security?

War-on-germs thinking brings results akin to those of the War on Terror, War on Crime, and the endless wars we fight politically and interpersonally. First, it generates endless war; second, it diverts attention from the conditions that breed illness, terrorism, crime, conspiracy theories, and the rest. “Terrain Theory,” says that germs are more the symptom than the cause of disease.

“Your fish is sick”.

Germ theory = isolate the fish.

Terrain theory = clean the tank.

We can normalise heightened levels of separation and control, believe that they are necessary to keep us safe, and accept a world in which we are afraid to be near each other; or we can look at it as an invitation to join a world where all of us are in this together? Take for example the issue of hoarding, which embodies the idea, “There won’t be enough for everyone, so I am going to make sure there is enough for me.” Another possible response might be, “Some don’t have enough, so I will share what I have with them.” On a larger scale, people are asking questions that have until now lurked on activist margins. What should we do about the homeless? What should we do about the people in prisons? In Third World slums? What should we do about the unemployed?

“How do we protect those susceptible to Covid?” invites us to move to thinking about “How do we care for vulnerable people in general?”

As Covid stirs our compassion, more and more people are realising that they don’t want to go back to the old ways; here is opportunity to forge a new, more compassionate normal. For a long time we, as a collective, have observed a sickening society. Whether it is declining health, decaying infrastructure, depression, suicide, addiction, ecological degradation, or concentration of wealth, the symptoms of civilizational malaise in the developed world are plain to see, but we have been stuck in the systems and patterns that cause them. Now, Covid has gifted us the possibility of a reset.

What do you think?